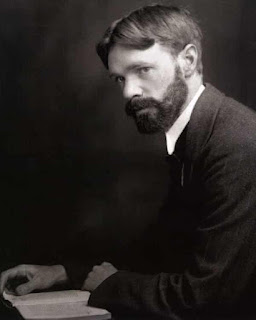

DH Lawrence

Up close and dangerous: the irresistible allure of DH Lawrence

For decades he was wildly out of fashion, now DH Lawrence is everywhere – from novels and biographies to a new adaptation of Lady Chatterley’s Lover

Lara Feigel

Mon 30 Aug 2021 04.00 EDT

When the clock struck for lockdown last March, many of us found ourselves condemned to live alongside people in more intense proximity than we’d bargained for. Flatmates, spouses, children were no longer occasional companions but a constant presence. For me, this has been the case with DH Lawrence.

Having committed to writing a book on him, suddenly I found myself sequestered with him. There was a time when this would have felt sexually charged. In my 20s, I fell for his vision of bodily life, as so many of his female readers had done. “His intuitive intelligence sought the core of woman,” Anaïs Nin wrote after his death. Visiting the shrine at Lawrence’s former ranch in New Mexico in 1939, WH Auden mocked the “cars of women pilgrims” traipsing “to stand reverently there and wonder what it would have been like to sleep with him”.

But for me, this phase has long passed. Since then, I’ve read the women – Simone de Beauvoir, Kate Millett – who have found him more dangerous. I’ve read the essays where Lawrence condemns “cocksure women”, celebrates the phallus, propounds ideas of racial hierarchy, rails against democracy and urges us to hit our children. Returning to these has felt claustrophobic during the months of our proximity, perhaps especially because intense closeness is a feature of Lawrence’s writing. He invites it from readers – his prose claims almost excessive personal investment. And his characters are often too close, engrossed in each other or captivated by an idea of themselves they have got from another person and can’t escape from.

There is so much in Lawrence that still entices. There are the best of his sex scenes – Ursula and Birkin kissing in Women in Love, unsure at first because they seem so far away from each other, and “it was like strange moths, very soft and silent, settling on her from the darkness of her soul”; or the richest scenes in Lady Chatterley’s Lover. But the challenge is to accept that his ugliness has to be seen as part of his vision, even when he seems most innocent.

From left: Oliver Reed, Glenda Jackson, Alan Bates, Jennie Linden and Eleanor Bron in the 1969 film adaptation of Women in Love. Photograph: Allstar/Cinetext/United Artists

Emerging from lockdown, I found it peculiar to discover that three other women had also been locked away with him. Rachel Cusk’s Booker-longlisted novel, Second Place, takes as inspiration Mabel Dodge Luhan’s memoir about Lawrence’s time in New Mexico. Dodge – a New York socialite before she settled by there with a Native American husband – invited Lawrence to stay, hoping he’d describe the area in his work. Her memoir records all that she and Lawrence put each other through. Lawrence put considerable effort into Dodge’s moral and sartorial improvement (persuading her to dress like his mother). But he vilified her in life and fiction as a wilful woman.

In Cusk’s novel, a painter called L is summoned to stay with a female writer called M in a house in the Norfolk marshes. She admires his work and wants proximity (and the book is set in lockdown). They remain frustratingly distant, yet are sometimes flooded by closeness so frightening that it nearly costs the narrator her marriage to Tony (the name of Dodge’s husband), and results in the kind of stripping down of selfhood that Cusk described in the Outline trilogy. “That plotting part of me – another of the many names my will goes by – now stood directly counter to what L had summoned or awakened within me … the possibility of dissolution of identity itself.”

Why does Cusk need Lawrence for this, given it’s an idea she’s had before? She has read him for years (and written powerfully about the awakening of modern womanhood in The Rainbow), but I think she needed this moment of reckoning with a revered male genius for the next stage in her autobiographical project. There are moving descriptions here of the slow growing together of two people in a second marriage, of the Norfolk marshes, and of the later phases of motherhood. The novel is more personal than the trilogy, more prepared to risk mess and humiliation, and Dodge’s own humiliating encounter with Lawrence seems to enable this, as well as something more mythical, wild and luridly plotted. Cusk’s narrator isn’t only Dodge, though. M has characteristics of Lawrence the writer, sharing his androgyny, his sense of the self as inhabited more fully when stripped of personality. In doing so she has more confidence than Dodge did in rejecting Lawrence.

Burning Man by Frances Wilson review – meets DH Lawrence on his own terms

Reading Lawrence this during lockdown – a time when, as a woman living alone with children, all my resources of will have been required – I resented his suggestion that female wilfulness is dangerous. I was grateful, reading the memoirs of women who knew him, when they resist him. “Your puppets do not always dance to your pipe,” the poet HD told him in her autofiction Bid Me to Live. And now, weeping, Cusk’s narrator tries to get L to understand “that this will of mine that he so objected to had survived numerous attempts to break it, and at this point could be credited with my own survival and that of my child”.

You To spend sustained time with Lawrence is to argue with him. Attraction to him has always entailed antagonism. He argued with everyone, and most of all with himself. Part of why he still matters is his love of ambivalence and oppositions – there was no thought that wasn’t enlivened for him by considering its opposite – and this can bring out equivalent energies in his readers. It’s very satisfying to find Cusk arguing with him, and to encounter Frances Wilson doing so in her eloquent and insightful but also determinedly belligerent biography of Lawrence, Burning Man, published earlier this year.

Wilson insists here that his novels weren’t his greatest works. Women in Love was not, she says, the “flawless masterpiece that Lawrence believed he had written”. I disagree with her larger judgments, but she constructs a thrilling romp of an argument that enables her to defend him as well, making a case for his essays as great works of art. She also defends him from disloyal friends. She dislikes the gloating Danish painter Knud Merrild who, despite knowing that Lawrence died of TB, described Lawrence in his memoir as “underdeveloped, athletically speaking”. “Few writers have been paraded naked oftener than Lawrence,” Wilson points out.

I too have done my share of defending Lawrence, as well as arguing with him. I have defended him, in particular, from Millett – another woman who’s been pushed into extremes of judgment by Lawrence’s excesses, arguing in her era-defining 1970 book Sexual Politics that Lawrence was one of the counter-revolutionary men thwarting feminism with their patriarchal fictions. Millett’s book was in some ways a necessary corrective to the cult of Lawrence, led by the Cambridge don FR Leavis, who championed his writing in his 1955 book as “an immense body of living creation” with redemptive power for humanity.

I have decided that Millett was spectacularly wrong about Lady Chatterley’s Lover, because she doesn’t read it as a novel. For the last few years, when I have taught Lawrence, my female students have fallen in love with Lady Chatterley’s Lover and then I have given them Millett to read and they have changed their minds, condemning Lawrence for reducing women to passive sexual objects. Yet Millett doesn’t take into account how fully Lawrence inhabits Connie as well as Mellors. This is one of the great portrayals by a man of a female character, up there with Emma Bovary and Anna Karenina. If, as Millett suggests, the male body is more lyrically portrayed than the female, then isn’t this largely because we see it through Connie’s eyes – because the female gaze is allowed to be as objectifying as the male gaze? Yet for Millett this is simply Lawrence making a woman preach his message. “Lady Chatterley’s Lover is a quasi-religious tract recounting the salvation of one modern woman (the rest are irredeemably ‘plastic’ and ‘celluloid’) through the offices of the author’s personal cult, ‘the mystery of the phallus’.”

‘To spend sustained time with Lawrence is to argue with him.’

For Millett, the gamekeeper is Lawrence. But in the novel, Mellors’ is just one, flawed point of view. There are times, I think, when Lawrence found him as overreaching, as foolish, as the modern female reader does. This is surely the case during his famously repulsive speech about his ex-wife’s clitoris – which he describes as a hard beak tearing at him with “a raving sort of self-will”’. When Mellors says this to Connie, I think Lawrence gives us room to see his speech as a partial view of a failed marriage. Connie doesn’t agree with Mellors – she pushes him to reflect on his own part in the difficulties. It becomes the kind of scene Lawrence does so well, portraying minute-by-minute gyrations of love and hate. They bicker; he tells her that women are self-important and she tells him that he is. She’s arranged to stay the night – it will be their first whole night together – but he tells her to go home. They make up, and go quietly to bed; it’s not till the morning that they undress and, in a glow of spring sunlight, she examines his body openly for the first time and they have sex.

After wrangling with Millett, it has come as a relief to read Alison MacLeod’s forthcoming Tenderness and to find in it a large-hearted celebration of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. MacLeod’s novel fictionalises two main time periods: the moment in Lawrence’s own life when he had a love affair with Rosalind Baynes, and the trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1960 (preceded by a hearing in New York). MacLeod moves, with dexterity and ease, between the heads of Lawrence and various defenders of the novel. These range from Baynes, to the defence lawyers at the trial, to Jackie Kennedy (an enthusiast of the novel, whom MacLeod imagines secretly attending the US hearing), to an FBI agent who falls for the book he has been charged with helping to ban.

It’s an ambitious sprawl of a book, splendidly extreme in its magnitude, yet always elegant; a defence of complicated thinking and embodied life. Lawrence’s novel propels the action and there’s even a scene from Constance Chatterley’s point of view. “The book must be read,” MacLeod quotes Lawrence writing. “It’s a bomb, but to the living, a flood of urge – and I must sell it.” MacLeod shows the flood of urge seeping through the lives of its readers, so that Kennedy, reading those lines about how “a woman has to live her life, or live to repent not having lived it”, wonders how her own existence can contain more life.

The rethinking of Lawrence led by Millett was necessary to help us get away from Lawrence as the prophet celebrated by Leavis and to rescue him from the prejudices he failed imaginatively to transform. Now, we are free again to confront him as we wish. And it turns out that Lawrence can still offer vital sustenance and provocation to his female readers, and can still produce in us rather drastic and exuberant fruits. We may have moved on in our sense of sexuality and gender, but he still speaks to so many of our desires – for many-sided complexity, for trenchant argument that remains open to contradiction, for books and lives driven by mood rather than plot, for selfhood freed of personality, for the awakened female gaze.